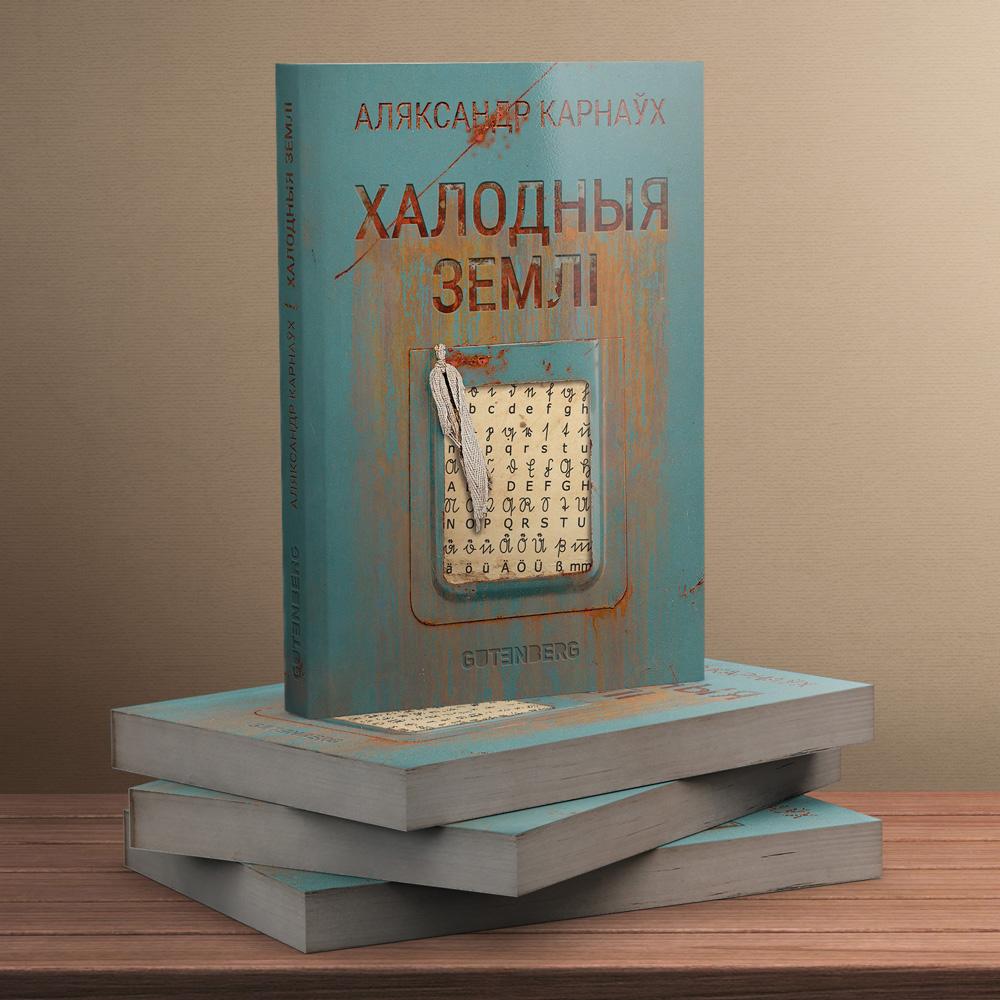

Gutenberg

Cold lands

Cold lands

Аўтар: Alexander Karnavkh

Low stock: 1 left

Couldn't load pickup availability

Мова: Belarusian

Старонак: 424

Год выдання: 2025

Месца выдання: Krakow

Вокладка: soft

Фармат: 14.5x21 cm

ISBN: 978-83-68016-38-3

University lecturer Antos loses his loyal friend, the beagle Argus. At the same time, his wife decides that their marriage has exhausted itself. Looking for a hobby to occupy his mind, Anton agrees to help his friend and decipher the text of mysterious notebooks found in an attic in one of the villages near Prorva - a swamp near which the protagonist's grandfather lived. The notebooks are written in Sütterlin, a now forgotten German script. Only individual words are decipherable, but the more the hero understands, the more anxiously he looks in the mirror.

If you live near the Abyss, it's easier to believe in werewolves than in uninterrupted mobile communication.

But our main character is a city boy. University professor Antos loses his faithful friend, the beagle Argus. At the same time, his wife decides that their marriage has exhausted itself. Looking for a hobby to occupy his mind, Anton agrees to help his friend and decipher the text of mysterious notebooks found in an attic in one of the villages near the Abyss - the swamp near which the main character's grandfather lived. The notebooks are written in Sütterlin, a now forgotten German script. Only individual words are legible, but the more the hero understands, the more anxiously he looks in the mirror.

________________________________________

QUOTE FROM THE BOOK:

The notebooks were different. Too different to be united by any common characteristic, word, or appropriate description. Some were thin, barely thicker than a regular school notebook, others thick , fleshy, like Piedmontese bulls. Paper covers, oilcloth covers, cardboard covers, notebooks without covers at all... Two dozen, no less. Folded haphazardly, because it was impossible to fold them straight, they leaned to one side and threatened to fall over, crashing down from the table onto the mocha and coffee cups.

— "Can I?" I asked.

— "Yes, of course," Yasya nodded, "take it and look. This is just part of it, so you can get an idea."

The manuscript lying on top was an ordinary notebook. Holding the edge with my thumb, I fanned it. It smelled of dust and old paper. Then I opened it at random. The light, checkered pages, without margins, had not yet turned yellow. They were written in a clear and dense handwriting: the lines ran in each line of the cells, the letters now tilted to the right, then straightened up, like those little soldiers on parade, then began to fall to the left, as if a wind had hit this detachment on the march and knocked down the ranks of brave Prussian soldiers.

— "It reminds me of a boustrophedon," said Yasya.

— What? — I didn't understand.

— This is the way of writing. Even lines go from left to right, odd lines from right to left.

But that wasn't enough! If so, then my bitter fate is that I'll have to keep track of the line numbers so as not to confuse the direction.

— So this is a boustrophedon?

— No.

— "Thank God," I muttered.

— What do you think?

I put the notebook aside, picked up another one, and flipped through it. It was the same picture: dense text, varying slant. Not a single picture, not a single familiar word. The rush of symbols made my eyes flutter.

— How to disassemble it?

— "It's a matter of habit," Yasya shrugged. "Nothing complicated."

The next bundle was made up of thin school notebooks, bound together, glued and bound together—nothing to add or subtract: a real book. Unlike the previous one, this one looked very old: it smelled of mold, and constellations of dark dots were scattered across the yellowed pages. A few headings caught my eye—short inscriptions of a few words between large sections of text.

— It seems they were lying in different places.

— "That's right," Yasya confirmed. "Some of the notebooks were hidden in a suitcase in the attic, we found a small number in the house among the books. The ones that were in the suitcase were better preserved."

— Maybe they're just newer? Is there any chronological sequence to them?

Metelskaya thought for a moment.

— There probably is, but I know nothing about it. To distinguish them somehow, I call the worst the Elder Edda, and the more dominant ones, the Younger.

— "Original," I said.

— "Pour me some coffee," Yasya looked at her husband.

He carefully filled the cup almost to the brim and carefully handed it to her. With a firm hand, Metelskaya raised the cup to her lips, not spilling a single drop, and took a sip.

— "Well, what do you think?" she repeated her question.

— I'm telling you, I agree.